The future is uncertain. You cannot predict it. But you can create it.

This is the conclusion of Alex Murell in his recent article The forecasting fallacy. The article is a great assessment of predictions about recessions, GDP, interest rates, exchange rates, media spend, and other stuff. He shows that the predictions are often so wrong that they are useless. His conclusion is to ignore such predictions.

This newsletter is all about predictions, so I cannot agree with that conclusion. At least not if simplified to four words like “You cannot predict it.”

Avoiding the Strawmen

Murell does not denounce all predictions. Weather forecasts for tomorrow are very accurate, for example. He works in “brand strategy, brand identity and brand communications” and the article is frequently addressing “marketers”.

Let’s stop clamouring over the ten-year trend decks. Let’s stop counting on the constant conjecture of consultants.

So, he targets predictions about geopolitical economic issues multiple years in the future. By the way, I agree with Murell here: If a consultant shows me a pretty slide with a ten-year trend into the future, I mentally dismiss it as bullshit.

A comment on Hacker News by diab0lic suggests this is about fat-tailedness, where surprising outliers are common:

Meanwhile the examples from the linked article are fat tailed processes. Recessions, GDP, interest rates, exchange rates. These are all subject to large discontinuous jumps. Anyone doing a 5 year rate prediction in July 2019 would have been required to predict the pandemic in order to accurately forecast.

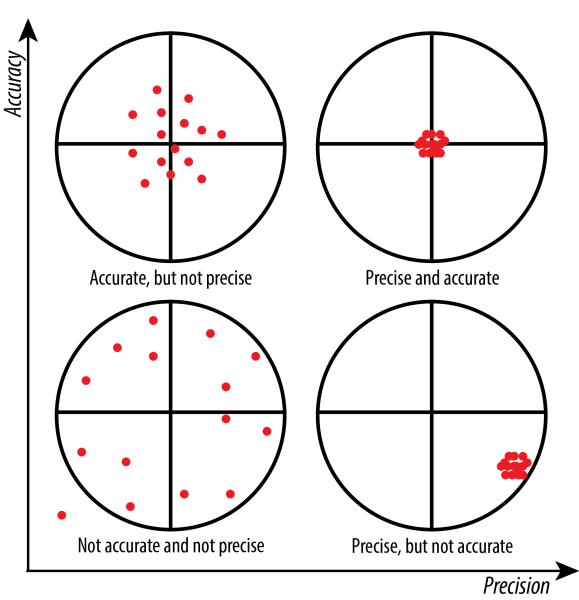

While I agree that fat tails often surprise people, it only means we have to lower our expectations about the precision of predictions. Being accurate is easy if you don’t need to be precise.

A closer look at GDP

My thesis here is that prediction markets provide the best forecasts. Metaculus has a forecast on “real GDP growth” for the next years. It looks quite boring.

How does it compare with the past? It looks certainly different.

Visually, Metaculus looks overconfident that GDP growth will be quite stable. However, the filled area is between 25 and 75 percentiles. In other words, we should expect a 50% chance that a value is above or below. Without checking the numbers, that looks in line with the Fed data.

One big problem with predictions is that the prediction is fine but the consumers of the prediction are unable to handle probabilities correctly. If a marketer sees a “ten-year trend deck”, will they look for the precision? If the prediction is honest, they will probably find out that the uncertainty is so high that the trend is not actionable for them.

Another problem are subtle mistakes. Murell writes:

Global GDP did contract in 2009 but by 0.7%, around half as severe as the forecast. In 2010, growth wasn’t sluggish but soaring. The global economy grew by a whopping 5.1%, two and a half times greater than the 1.9% predicted.

Maybe there is a mistake about the 2009 data (e.g. nominal vs real GDP). I did not check very closely. The 2010 forecast is still off as described, so Murell’s point stands.

A third problem is that such predictions can be self-defeating. When an institution (like IMF or World Bank) publishes such predictions, they expect governments to react. This changes the outcome and they have no incentive to include this in their models. In other words, accuracy might not be the only goal. Influence is another one.

Prediction markets have an advantage over institutions here since they incentivize accuracy. If someone intentionally introduces bias, other traders profit by correcting it. Activism and lobbying on prediction markets is possible but very costly.

What is the Point?

So far, I have not directly argued with Murell’s thesis. What exactly is it?

If you want to be successful over the next 10 years, start building a competitive advantage over the next 10 months. If you want to win tomorrow, start tilting the table today. If you believe things should change in the future, put pen to paper in the present.

I would phrase it as: You will be more successful, as a marketer or company, by actively shaping the future than predicting it.

Ironically, this is a prediction just like GDP growth: Long-term, geopolitical, and fat-tailed. Also, you cannot completely neglect either one since both are needed. So Murell thinks about the balance between them and apparently believes that most marketers weight the prediction side too much. As a thought leader (as a blogger, I assume he desires that title at least a little) he tries to shift their mindset away from forecasting and towards activity instead.

The article does not provide evidence for this thesis. While it argues well how bad predictions can be, the constructive aspect is only inspirational phrasing. There needs to be evidence to reject the alternatives “predicting is more successful” and “it doesn’t matter”. Maybe the best strategy would be to rather invest in your agility, so you can react more quickly when inevitable changes come along? Personally, I don’t really believe in Murell’s thesis but I don’t have evidence either.

What can we do now? We can bet on it.

What is My Point?

What I don’t like about the article are sentences like this:

We can’t predict recessions, GDP, interest rates, exchange rates or media spend.

I believe we can predict them.

The real question is not “if?” but “how good?” Unfortunately, this is a more complicated question. The answer “yes” is easier to use than “72%”.

One the one hand, Murell is right in criticizing predictions. In some sense all predictions are wrong if you demand a 100% accurate and precise prediction. On the other hand, if you ignore predictions all together, you throw out the baby with the bathwater. I want more prediction markets, so predictions become better. Predictions are useful even if they are not perfect.

Unfortunately, better predictions are not enough. We also need better consumers for the predictions. We need to figure out when and how to use predictions well. Some knowledge about statistics is helpful but there is also tacit knowledge of feeling the difference of a 10% and 20% chance.

In the end, predicting is inevitable because every decision you make involves a prediction what will happen as a result of that decision. Predictions can be made in a fraction of a second or laboriously. In the end, all that matters is how good the decision is.

This is what this newsletter is about.

The Vox Future Perfect team made some predictions for 2024 and they used probabilities.

If you want to track your resolutions but not publically, I just discovered Fatebook which allows private and public predictions.

Probably until next week, my accurate readers! 😊